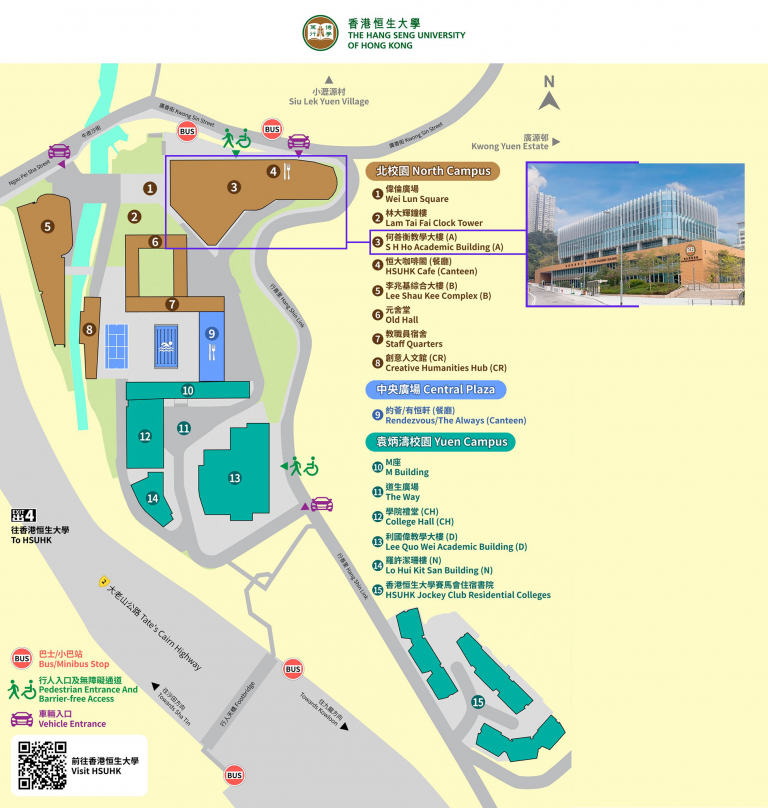

Main Venue: A315 (Pong Hong Siu Chu Lecture Hall), 3/F, S H Ho Academic Building, The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong

9:30am

Registration

A315

10:00am

Welcoming Remarks

Professor Joshua Mok (Provost and Vice-President (Academic and Research) & Dean of Graduate School, The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong)

Opening Address

Dr Chris Li (Assistant Professor, Department of Social Science, The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong)

A315

Group Photo

A315

10:30am

Keynote Lecture

Food Justice in East Asia – More Challenges and New Direction

Chairman: Professor Kao Lang (Professor and Head, Department of Social Science, The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong)

Keynote Speaker: Professor Chang Hung-hao (Distinguished Professor and Chair, Department of Agricultural Economics, National Taiwan University)

A315

12:00pm

Lunch

Shek Mun

2:00pm

Panel 1

From Food Insecurity to Food Injustice: Philosophical Perspectives

Presenters:

Of the three basic material needs of human beings – food, shelter and clothing – none is as fundamental as food. Nothing drives a population into social upheavals, shakes the family unit to its foundation and turns a person into a tinder box, as much as the lack of food to eat. This paper is propelled by the obvious and unfortunate food insecurity in Africa and seeks to draw implications from this state of affairs for Africa as a continent. Employing phenomenological and hermeneutic analyses, the paper, however, goes further to show that food insecurity in Africa has far more deeper implications for the global community, world peace, migration, political stability as well as human survival and flourishing. The paper posits that food insecurity is a classic phenomenon that requires the open – minded and presuppositionless attitude of phenomenology. The paper also establishes the correlation between socio-political insecurity and food insecurity when a population cannot feed itself; between the right to life and the right to food; as well as the self-inflicted underdevelopment inherent in the employment of hunger by leaders in Africa as a weapon of subjugation and surrender. The paper traces both the material and logical consequences of the phenomenon of food insecurity at the social, political, economic, mental, and ontological spheres with examples from some African States. The paper concludes by arguing that in spite of the challenge of food insecurity in Africa, its implications FOR the global community requires a united approach in order to ensure food justice for humanity as a whole.

KEYWORDS: Africa, Anger, Hunger, Food Insecurity, Implications, Phenomenology.

In this talk, I will investigate the hunger problem in Africa and attempt to draw a correlation between food production quantity and distribution patterns. Hunger is a serious problem in our world today. It is much more so in Africa south of the Sahara. However, this scenario reeks of irony because statistics show that the world is producing more food than at any other time, perhaps even more than the global population needs. Thus, why do we still grapple with the problem of hunger amidst plentiful food production? Why is hunger a philosophical problem? Is there food injustice in our world today? Using an argumentative approach and conceptual and statistical analysis, I will interrogate food production and distribution patterns to unearth any challenges that engender the problem of hunger. I will further analyse the preceding to determine whether such might implicate what can be called food injustice.

Within the literature on food justice, philosophical works are less prevalent compared to those from other disciplines. This paper highlights two contributions from one school of thought in political philosophy—left-libertarianism—to the literature. Left-libertarianism can be understood as asserting that individuals have a right against dominating relationships, whether they occur within or across national borders, and bodily sovereignty, which protects against domination over one’s choices to effect and experience bodily changes. The paper first examines how the right against dominating relationships serves as a critical conceptual tool for analyzing the pre-institutional domination of powerful states over weaker ones in the realms of food trade and national agricultural policies. Second, the paper argues that left-libertarianism’s emphasis of greater moral weight of respecting bodily sovereignty over combating other problems of justice implies that food sovereignty shares the same status, for food sovereignty is a necessary condition for bodily sovereignty, considering the organismal nature of human bodies.

A315

4:00pm

Break

A315

4:15pm

Panel 2

Understanding the Political Economy of Food Systems

Presenters:

Dr Liu Tong (National University of Singapore)

The environment and climate are key to agricultural production and food security. Many parts of the world are threatened by critical environmental and climatic challenges, such as pollution, wildfires and prescribed burning, extreme temperatures, floods and droughts. These challenges impair human capital and disrupt economic activities in agriculture, manufacturing, and services at the local, regional, and global levels. Understanding the causes and consequences of these issues is crucial for evidence-based policymaking for adaptation and mitigation. However, relevant causal evidence remains limited due to empirical challenges, calling for more research from multiple disciplines including natural sciences and social sciences. This talk will cover some recent research on the interactions between the environment, climate, agriculture and food security from an interdisciplinary perspective. Firstly, we will examine how agricultural practices affect the environment and climate, and how it further affects humans, agriculture and the economy. We will then explore the roles of several potential solutions in adaptation and mitigation, including governmental policies, market-based instruments, and nudging. We will conclude by discussing the political economy of regulation within and across borders.

Dr Kwok Chi (Lingnan University) & Mr Derek Tai (Lingnan University)

Externalizing production costs has long been a central strategy in the labor platform economy. It allows platforms to lower their service prices and increase competitiveness. This strategy involves shifting costs that should be borne by platforms onto third parties. In the political theory literature on the platform economy, most attention has focused on what Bieber and Moggia (2021) term “risk shifts”—the externalization of labor protection costs onto workers themselves. In other words, labor protection responsibilities have been transferred to society and individual workers through the flexibilization of employment. As a result, the primary focus on cost externalization in the labor platform economy has been on remuneration, insurance, and temporal costs. In this essay, we explore a relatively understudied area: platform firms’ externalization of spatial costs. Specifically, we examine spatial externalities in urban food delivery, with a focus on how food delivery platforms shift the costs of traffic, parking, and access to public spaces. The nature of fragmented working hours, time-sensitive tasks, and door-to-door service makes public space essential for food delivery workers’ routines. Yet, food delivery platforms rarely implement formal policies to cover the costs associated with public space usage. As a result, these spatial costs are often externalized to local communities or the food deliverers themselves. The essay highlights the direct impacts of the platform economy on public space and argue that social spatial costs are a fundamental aspect of the flexibility offered by the labor platform economy.

Dr Chris Li (The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong)

This paper explores a structural tension shared by the liberal and the socialist theoretical paradigms of political economy, as manifested in the works of Adam Smith and Karl Marx, namely the incompatibility of their optimism in the progress of productivity, on the one hand, and their ideal vision of a decentralised economy, on the other. Both the pre-industrial ideal of Smith and the post-industrial ideal of Marx posit a future of extremely high productivity, while failing to account for how this might be achieved without intensive capital accumulation, or the problematic consequences of intensive capital accumulation to the environment. This tension is especially manifest in their discussions on the future of the food system. This paper argues that the tension could be resolved by rethinking the meaning of wealth and productivity in light of the recent discussion on degrowth. In practice, this would imply a reorganisation and combination of both urban production and agriculture in a way not relying on intensive capital accumulation. Situating in the current successive disruptions of capital accumulation caused by geopolitical trade and military conflicts, the discussion of this paper might provide some hints for a way forward to a more progressive future.

A315

6:30pm

Conference Dinner

Shatin

Main Venue: A315 (Pong Hong Siu Chu Lecture Hall), 3/F, S H Ho Academic Building, The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong

9:00am

Registration

A315

9:30am

Panel 3

Challenges of Food Insecurity to Global Democracy

Presenters:

We live in two worlds- the world of ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’. One of the primary things that the poor don’t have is food. Food relates to human dignity, which is inseparable from democracy. This is a triad. A triad refers to three things of people that are considered as one unit. Justice is an integral part of dignity, which is also an integral part of democracy. The removal of either of these will throw an imbalance. In our present global and local contexts, this triad seems to be conveniently forgotten in favour of the powerful. Those who are weak, vulnerable, marginalized and excluded from the mainstream are also poor, powerless, and voiceless, and forgotten. Encountering this reality is not a choice, but a responsibility towards fellow humans.

Food Justice goes beyond legal perspectives. It is an integral and ethical state of any society that believes in ‘community,’ and communities are not built by laws, but through relationships. While the state can guarantee certain minimum provisions for food justice, it does fall short of a holistic understanding of such a justice in terms of community. When communities are polarised, then food justice cannot be fully realized.

Human dignity is intrinsic to each human person and is inalienable from the personhood of each person. This dignity needs to be upheld by every government and every community. Food as a basic right and need, when denied for whatever reason or is inaccessible or made inaccessible, can affect the realization of this human dignity.

Democracy is about reclaiming and restoring human dignity and empowering and enhancing the state towards caring for this dignity. It is undemocratic if an elected government cares less for this fundamental requirement.

Taking the case of India, this triad would be critically discussed from a philosophical perspective of/with the poor, and would bring forth some insights into the issue, hoping to rediscover and reclaim the triad aforementioned. This would be done in four angles: common narratives found in political, social, and religious discourses, conceptual frameworks, current practices, and future directions.

Dr Wong Muk-yan (The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong)

The emergence of electoral authoritarian regimes represents a significant and novel challenge to democratic systems. Unlike traditional authoritarian regimes that rely on coercion, economic patronage, or propaganda, these governments consolidate power through ostensibly legitimate electoral processes. By presenting themselves as strong leaders capable of restoring political and economic stability, they attract the support of populations experiencing chronic uncertainty and anxiety. In such contexts, voters may prefer the stability promised by an elected authoritarian leader over the perceived weakness of democratic governance or the unrestricted power of dictatorships. (See Matovski 2021)

Food insecurity, defined as the perceived or actual unavailability of food due to price instability or future risks to food access, offers a strategic opportunity for these regimes. Leaders who claim they can stabilize food supply chains often gain significant popular support. Even when such leaders fail to deliver on their promises, voters may continue to support them, fearing that a change in leadership could exacerbate food insecurity. Numerous examples illustrate this dynamic: in Venezuela, government used programs like CLAP (Local Committees for Supply and Production) to distribute subsidized food packages according to political loyalty; in Zimbabwe, food aid is often conditional upon visible support for the ruling party, such as attendance at rallies or participation in pro-government activities. Communities that support opposition parties may face deliberate delays or reductions in food aid; and in Thailand and Uganda, promises of agricultural support are exchanged for votes. The exacerbation of food insecurity caused by crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine has further fueled the global trend of democratic backsliding and the rise of electoral authoritarianism.

Dr William Biebuyck (Georgia Southern University)

This paper explores the possibilities inherent in developing a more pluralist or ‘hybrid’ model of global food ethics and transnational agrarian cooperation. The intellectual starting point of the project is a belief that the problems, challenges, and effects of our globalized food system present a domain of such complexity, specialization, and differentiation that no single framework can offer a viable ‘way forward’ in terms of generating a singular and workable set of goals, principals, and strategies. In short, the realities and challenges are too numerous, unique, and differentiated across the global agrifood landscape. After all, contemporary agrarian and food politics has become closely intertwined with those core aspirational doctrines informing global governance; such as sustainability, human rights, decolonization, human security, economic justice, and international law. In this initial sketch of a hybrid global food ethics, three paradigms will be explored in terms of their potential for providing the diverse intellectual foundations required for a genuinely pluralist ethics: (1) the ‘integrative’ human development and SDG model (2) the governance ‘school’ premised on functional cooperation and technocratic expertise, and (3) the food sovereignty literature/movement that advocates for the democratization and localization of food systems.

A315

11:30am

Lunch

Fo Tan

1:30pm

Panel 4

Food Policies and Food Movements: Regional Experiences

Presenters:

This research introduces efforts of South Korean citizens, local government, and the experts in bring the issue of food justice into Seoul Food Plan and Food Strategy. While S. Korean development based on industrial growth has been remarked as a case of success, there are many problems including serious urban-rural imbalance, extremely unstable food security, and food injustice nationally and locally. In order to deal with issues, there have been growing efforts by citizens and experts to build a new food governance. Their collective efforts along with a progressive leadership had enabled Seoul, the capital of S. Korea, to institutionalize food plans and a food strategy, which included various programs to bring about food justice. One of the most impressive examples of these programs was ‘Urban-Rural Coexistence for Public Procurement’ which tried to make social and economic ties between districts of Seoul with rural towns around the nation. Yet, this progressive program now is facing great difficulty under conservative market-oriented regime both at the national and municipal level. I analyze the rise and decline of food governance centered around food justice and food security in Seoul, and its impact on other parts of S. Korea.

Dr Ardi Priks (European Commission)

European Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) is one of the most important and controversial policies of the European Union, and it is far from clear whether the 60-year-old policy is available to deliver food security and justice. In part, the question remains unsettled because there are many different understandings of what could constitute a secure polity, not to mention a food-just society. This paper provides a brief overview of the main characteristics of the CAP. The paper then analyses the policy from the perspective of normative agricultural economics. Declarations of prominent academic European agricultural economists are used to define what kind of agricultural policy would be normatively desirable. It shows that the CAP fails to live up to the expectations. This is so because domestic food production is neither necessary nor sufficient criteria to provide food security in the sense of supply. When it comes to justice, it shows that the CAP’s highly divergent direct payment—levels of which vary greatly both between farmers of the same member state and between member states themselves—can hardly be considered just. This draws attention to the urgent need to reform the CAP further.

DISCLAIMER: Views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. They cannot, in any way, shape or form, be attributed to the European Commission.

Dr Daisy Tam (Hong Kong Baptist University)

Hong Kong’s food system exemplifies many of the world’s global cities – as an economic powerhouse operating in a 100% urbanized environment, the city’s produces almost none of the food it consumes, importing 95% of the food we eat while throwing out almost 3200 tonnes of food a day to landfill when 20% of the population lives with food insecurity. This narrative often frames food rescue as a win-win-win solution, good for the environment and caring for the poor.

While repurposing surplus food is key to sustainable development, there are many gaps which has not be addressed. In this talk, I would like to draw from my work in academia and my experience of starting a food rescue charity to share, reflect and examine the multiple dynamic relations of care. Not all care is good care and attending to the nuances opens up alternatives of actioning care. I will be drawing concepts and framework from feminists writers of care, Eve Tuck’s notion of desire-centered research, and also offer my own reading of parasitic ethics as I talk through how I developed my practice-based research in urban food systems.

A315

3:30pm

Break

A315

4:00pm

Roundtable Discussion

Practitioners meet Academics

A315

By Bus

Tate’s Cairn Tunnel bus stop

Bus:

272S, 277X, 274X, 277A, 275X, 277E, 277P, 286M, 307, 307P, 373, 680, 680A, N680, 681, 681P, 682P, 673, 673A, 678, 74X, 75X, 80X, 82P, 82X, 83X, 84M, 85C, 85M, 89C, 89D, 89X, X89D, 85X, 88, 74B, 74D, 74E, 74F, 74P, 90, 96, 97, N307, T277

HSUHK (Kwong Sin Street) bus stop

Mini-bus:

65A, 65K, 808, 808P, 806A

Bus:

83K, 83S, 86, N182, 281A

Driving Route

Please refer to the instructions here: https://www.hsu.edu.hk/en/visitors/campus-map/